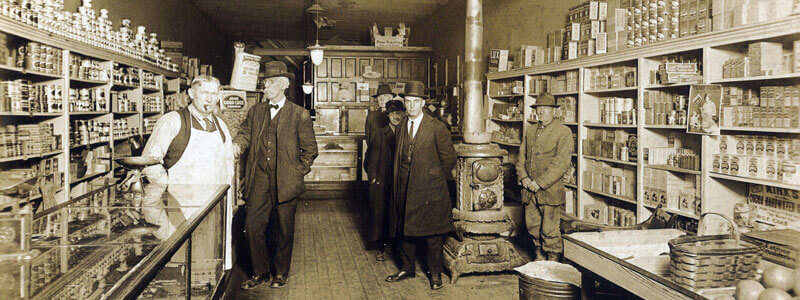

The proverbial Barcelona botiguer, diligently manning (or womanning) the family boutique, is often championed as the last and most noble bastion of the city that was. Without such folk, wringing their hands as they peer out across countless marble countertops, we are told Barcelona would not be the same. Our neighbourhoods would lose all their character, they say, our streets would become cold and lifeless. Without the local shopkeeper, we hear, we’d be condemned to the clinical interiors of franchised commerce and hypermarkets, with their banks of fluorescents above and aseptic shelving below. Without our old-timer stores we would lose, they tell us, our very identity.

Hardly anyone in Barcelona is against a locally-owned shop, diligently run by the proprietor. Hardly anyone says anything bad about them. Even if we don’t go in, we love how their lights bathe the streets ochre, warming our passing as day turns to dusk. But ask Barcelonans about the most insistently irritable sector of their society and shopkeepers come to mind. Some seem cool and wise, but then get inarticulately opinionated; usually tolerant with customers, they are prone to narrow-minded rants as well; at first they’re discreet, but end up sticking their noses into everyone else’s business. The legions of neighbourhood merchants can be a real nightmare at times.

Back when I cared about “the news,” I bought my paper from a stand on Paral·lel. Talkative and well-read, the seller obliged me for years with friendly chat. Then one rainy winter his mood turned dark: just beyond the reach of his awning a broken paving stone would fill up with water, splashing his customers as they stepped on it. It drove him nuts. It became his daily excuse to rail against city hall, complain about taxes, make xenophobic remarks and generally behave like a reactionary. Our conversations ended. That was when it finally occurred to me El País was not a progressive newspaper after all.

Sometimes you wonder what’s buzzing around in their heads. When we say you’ve got a bee in your bonnet it means you’ve gotten terribly agitated by something petty blinding you to the big picture. There are so many bees in the bonnets of Barcelona botiguers that local apiculture is singlehandedly reviving the world’s declining hives.

Thing is, sometimes you wonder if someone got things buzzing for a purpose. For years, right-wing parties like Convergència convinced merchants they were special, winning their political support in a rather vicious circle of clientelism. Barcelona shopkeepers willingly turned themselves into an army of street-level propagandists, buying into the absurd tale of their patriotic importance. Then, when they transfer over their rental contracts to recent immigrants, the story ends; not every merchant in Barcelona is special.

If things are changing, it could be because Barcelonans are coming to appreciate other legitimate forms of exchange, like barter, trade and buying direct from producers. Things like sharing, and giving gifts. Dynamic ideas like street vending are trying to make inroads, despite decades of irrational grudgery from those owning stores.

In Anarchism and the City, his marvellous book on Barcelona street politics in the tumultuous ‘30s, Chris Ealham describes how a nascent Esquerra Republicana sided with the petit-bourgeois merchants against the thousands of good Barcelonans making a living by selling their wares in public space. The revolutionary pulse of Barcelona streets had its enemies within. Eighty years later things have gotten worse, with storekeepers struggling to guarantee their monopoly. Part of this, disgracefully, seems to involve picking on the sub-Saharan Africans selling top manta, a grossly overblown concern. Sometimes you feel like asking your trusted local merchant, as much as you love him, to hush up, get back behind the till, and give it a rest for once.