Most Barcelonans haven’t a clue where their city begins and where it ends, which is why a lot gets called Barcelona when it’s not. While it borders ten neighbouring towns, few can draw the lines. Some have heard of a long street called Riera Blanca flanked by the capital and L’Hospitalet, but who’s ever actually been there? This only goes to show that when making reference to the city, we rarely refer to its substance in cartographical terms. Barcelona is more like an idea.

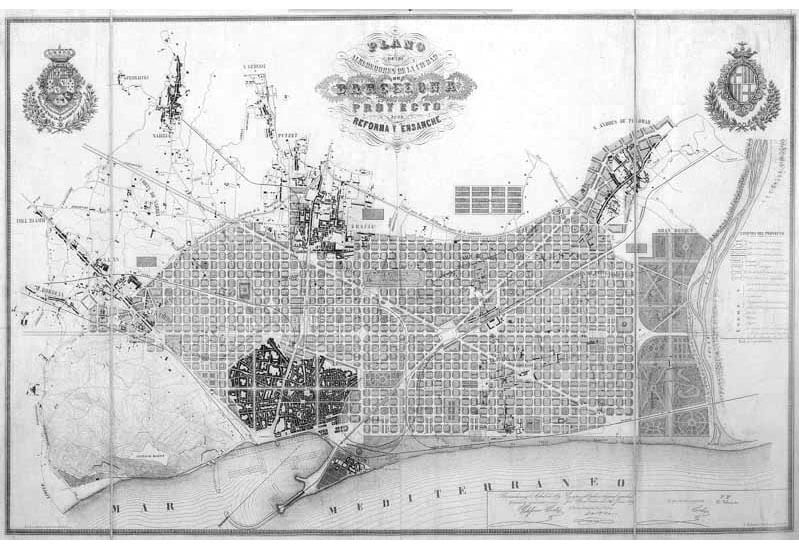

Good residents are unaware their beloved city spent decades greedily gobbling up its neighbours, apparently to widen its tax base. In the 19th century almost half of what is now the municipality was in other hands, until a royal decree in 1897 allowed for the annexing of Sants, Les Corts, Sant Gervasi, Gràcia and Sant Martí, no less. Since the king kept saying yes, Barcelona kept asking for more: Horta fell to another decree of 1903, Sarrià in the 1920s. Such lust for expansion meant Barcelona kept stealing slices of its neighbours’ pies, like part of Collblanc from L’Hospitalet, and Bon Pastor from Santa Coloma. There was a time the elderly from such places would ceremoniously announce “I’m going to Barcelona,” when in fact they were already here.

Barcelona went to preposterous extremes to control its hinterland, like when a Collserrola enclave called Santa Creu d’Olorda, named after a chapel, was conveniently absorbed even though it did not even share a border. In 2014 Molins del Rei officially petitioned to have it returned, and so fill in that unsightly hole in its municipal map.

You’d think our neighbours would be bitter, but they are not, even lying about their capital connections. Saying you’re from Barcelona when your home is in Montcada is fine, though when it comes to blurring lines, no Barcelonan errs in the other direction. Folks in Les Corts don’t fake being from Esplugues. It’s the same the world over, especially when the aura of a hip metropolis is in play. Half of New Jersey will say they are from “New York” rather than having to apologize for residing in an industrial wasteland. No student goes away on an Erasmus and tells classmates they’re from Badalona.

In earlier times cities had walls, and the lines were clear. You could pay a fee and they’d open the gates, they could chuck you out if you behaved badly. Enemies knew just where to attack, devising funky catapults, just like in the movies. Looking at the Roman walls, you can imagine some Germanic horde sneaking up one morning in 411 AD to harass retired centurions. In times of peace the areas just outside were veritable hotspots, with all kinds of unusual and illicit activities going on. The Ramblas used to be one of them, when the medieval wall ran down the Gothic side. Nowadays the very definition of “edgy” has lost its literal meaning.

As Barcelona is greater than the sum of its parts, its self-esteem is obnoxiously intact. No bordering town is really envied (however moneyed Sant Just may be) and none is feared (with Sant Adrià now gentrified). Not a single name of a neighbouring town resonates in any way: people don’t even tell jokes about them. In terms of cultural meaning, only Barcelona has generated an unequivocal identity, forged out of history, fertilized by cultural lore, propagandized in the interests of worldly distinction. The rest don’t come close. This explains why not a single foreigner in the history of world tourism has ever gone on holiday to Santa Coloma.

But maybe it shouldn’t be this way. Imagine if the outskirts were to take a step up: they could set up a blockade, they could do “Day without Traffic” and trap everyone inside. Or, less vindictive, they could strive to be cooler than Barcelona, attract young people, like by not persecuting culture or building accessible housing. It’s a testimony to the capital’s narcotic allure that, being so damn close, not one of Barcelona’s neighbours has even tried.