On any given day, far from the center of any presumptive art scene in Barcelona, one of the world’s last practitioners of impressionism picks his spot to paint in a park. His satchel of cost-cutter acrylics and sketchpad in hand, Miguel Palau Figueres makes the short walk from his apartment within earshot of the soul-crushing crudity of Avinguda Meridiana to the Parc de la Pegaso in Sant Andreu. He selects a bench, adjusts his piercing gaze to screen out the beer cans and dog shit that litter the foliage and sinewy lake surrounding him, and, like a kaleidoscope turned to the light, his canvases fill with color.

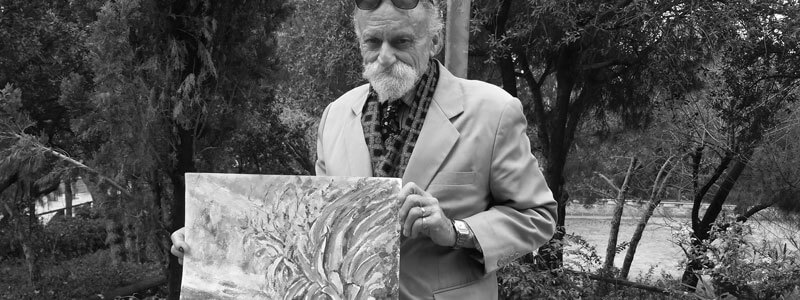

“I’ve painted since I was old enough to think. I paint landscapes, portraits, a little bit of everything. I’ve come here forever.” Palau has been painting since the age of 12. Seven decades on, he cuts the figure of a dandy in graceful decline. He pinned down his wiry hair with a pair of sunglasses perched on his head, whose bottom third is covered by a white puff of bushy goatee. A beige jacket, dark tie and a long, blue-and-red checkered scarf contrasted with the pair of sneakers that helps him negotiate the dirt paths crisscrossing the park that replaced the old Pegaso truck factory 30 years ago. I had seen Palau painting or sketching several times while I walked my dog. “Are you a painter?” Pausing from feeding a muffin to some pigeons, he told me that yes, he was indeed. He invited me to join him on the overlook where he had decided to set up shop with the fragrance of a morning rain shower still in the air. “I like to come paint when it rains. When everything is wet and the people are all hunched over,” he said, before showing me a large selection of his drawings and paintings that he had with him. “I’m like a turtle. I can’t help it.”

Instead of his given name, the signature “Flamarion” appeared in large letters across the bottom of the canvases that belonged to a school of painting which reached its heyday two centuries ago. “Impressionism, impressionism,” said Palau, as if repeating a pledge.

In a time where the contemporary artist must be versed in digital technologies, should boast a nose for the market and self-promotion, and is wise to be cynical about any claims to such a thing as Beauty, Palau is a holdout from when art still imbibed concepts such as contemplation of Nature and getting one’s hands dirty. When asked about the current state of the art world, his eyes glimmered. “Today there are painters who do things with computers, but not many who can paint directly on the canvas,” he said. “I give a lot of credit to whoever invented the computer, but not as much to those who came after in the chain.” Working in acrylic, water colors, pen and pencil, he keeps things simple, and within the limits of his pension. “I paint with very cheap paints. €1.50 at the Chinese. Red, blue, yellow, white and black, with these five colors you should be able to make all the rest. That is the primary technique.”

Palau, and the scores of nameless artists like him, don’t fit into the triangle of artist-art-audience that constructs an art scene. Instead, in their solitude and with their works unseen, they add a hard-to-define quality to the spaces they privately transfigure. When I see Palau painting in the park, I can’t help imagining what has caught his eye. I am challenged to bracket off the world’s imperfections and cast a protective halo around the good amid the rubbish. It may have something to do with what Palau said when I left him on the hilltop: “I don’t do this for money. There is more to life.” Sometimes I think I see it without any prompting, when the sun rays cut through the tree tops at just the right angle.