Barcelona is one of many seaside towns with a booming port and no natural harbour. The two need not always go together, since modern ports are the stuff of megalithic breakwaters, enthusiastic landfills and piers wider than the most elegant shopping boulevards. If need be you could add an airport and throw in some bridges; you could stick a casino out there, you’d be competing with Macau. A port need not be predicated on the geographical conditions that once invited storm-torn ships to find haven for the night, stretching their prows past a welcoming lighthouse into the calmer waters of a protected cove. The proverbial sanctuary of early mariners can now be done artificially. Ports can be built on pretty well any body of water, geography be damned.

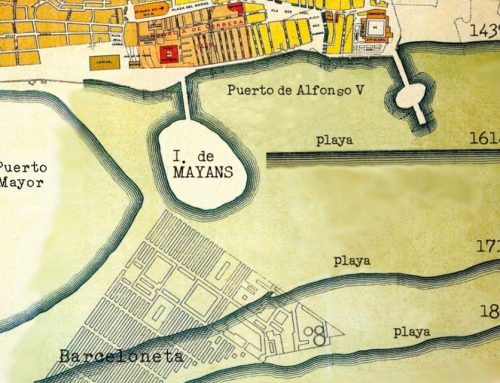

Early maps tell us that the coastline in front of Barcelona was basically straight, with a little half-circle blip in front of the bricked Tinglado, right where the luxury yachts now bob. Barceloneta did not exist; the little crescent of jutting land turned back to a section of marshy beaches, continuing north from somewhere opposite the Estació de França.

For the early Romans colonizers, even that was not enough: they had their port quite a way off, at a minor indenture near the south-west corner of Montjuïc cemetery. We can only imagine this if we remember that two millenniums ago the sea was much closer in. Transportation was around the backside of the mountain, by road, entering into the original city from above. Most of the massive hewn stones used for the walls came from the old quarry nearby, where we now find memorials to the Holocaust, Civil War volunteers and former Catalan president Lluís Companys. Barcelona had a port, but you entered the city by land.

It breaks every Spanish law affecting construction along the coastline. It has its own police, like a pioneer town might hire its own sheriff.

By the Middle Ages the activity of the port had moved to the more logical location facing the city, as the civil Gothic architecture of the Maritime Museum attests. If an enemy ship appeared, you could shell it directly, which was much more convenient. A working port conceived for the movement of merchandise and naval expeditions of a military nature was established; it was from here that the Kingdom of Aragon’s Mediterranean empire was launched. It sounds quite impressive, but in the early 1600s Cervantes still described it as a bit of beach with a bunch of boats, in the famous scene where Don Quixote sees the sea for the first time, then loses yet another ill-sought joust, this time on Barcelonan sands. The subtly-tiered wooden planks imitating a sandy shore on the Maremagnum leisure pier are an homage to this sabulous past.

Successive centuries saw a rampart built, separating populated Ciutat Vella from the port. Later on, it was all ribboned with railway lines, then walled off. Up to the 1980s it was still like this, inaccessible to anyone with no business to do there. Yet the port still spilled its human-side over into the nearest part of the city, with seamen and dockworkers and sharply uniformed navy lads wandering the lower Raval.

With the building of Maremagnum and the World Trade Centre, the working port was shifted down the coast, and there is hardly any physical evidence left of it in the town; I don’t even know if Bar Kentucky still has those postcards behind the bar of American frigates and destroyers, since I haven’t been in ages.

Nowadays, the Port of Barcelona is run by an authority controlled by the ministry in Madrid, which is why Maremagnum can keep any shop hours they want or permit a hotel like the “vela” (the W Barcelona), which otherwise breaks every Spanish law affecting construction along the coastline. Loading and unloading crates and containers, the stevedores’ union exerts its own form of control, rarely wielded (though a few years ago they went on strike). It has its own police, like a pioneer town might hire its own sheriff. Cruise ship passengers are moved in and out through an access corridor, along a new sea wall and over the white bridge in front of that part of Montjuïc known as El Morrot.

The route is actually public. Anyone can get an inside view of the port by taking it, but few Barcelonans do; it feels desolate, forgotten. The working port, like so many functional pieces of our world, holds little fascination for a generation disenfranchised from the material “how” of our existence. Barcelona no longer lives with its back to the sea, it lives with its back to the port.