For decades the success of the Spanish democratic transition was widely attributed to the ability of so many divergent parts to agree. Instead of digging up the past, setting up tribunals to take the perpetrators of totalitarian crimes to trial, Spain chose to chill. Franco-era torturers lay back on Costa del Sol beaches while their victims did the same in unmarked graves, and no one dared complain. Rocking the boat was a threat to the delicate balance keeping the new democracy afloat.

[quote align=»left»]The culture of pacts, where the greater good overrides what you really believe, has been especially strong in CataloniaThis tale of harmony seems to be coming unravelled, with economic collapse and political corruption testing people’s patience. Some say we need a new, more fractious transition, where everything gets put back on the table, like it or not. Yet however drastic the changes proposed, citizens still value social peace.

The culture of pacts, where the greater good overrides what you really believe, has been especially strong in Catalonia. When pundits spoke of the “Catalan oasis”, they were referring to economic buoyancy and cultural verve, but also to political and social concord. In Catalonia, and especially Barcelona, everyone is asked to make an effort to get along. Well-off and working class, uptown and down, immigrant and Catalan purebred— what they all have in common is just that: the word “and”. The longest governing party in Catalonia even had an “and” in its name (Convergència i Unió, just now split). So much addition makes things rather pleasant. Even when you disagree you still have to be nice about it, and politicians never know when an electoral minority or common cause could push them into coalition with a rival.

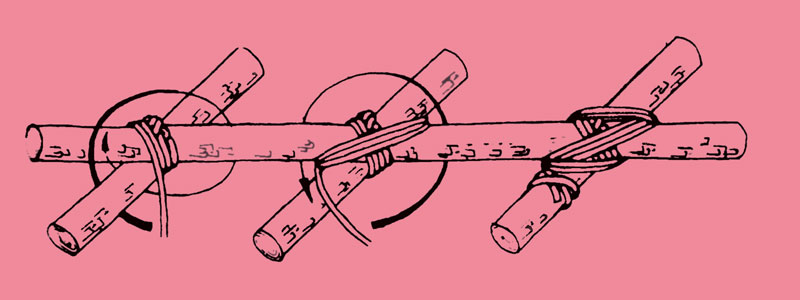

Many reasons are given for this talent for acquiescence. One is that Catalans have a “strong associative fabric”, a textile metaphor that once made sense in a land full of garment mills. The factories have closed, but the logic holds. Private associations abound, dedicated to sports or culture, folklore or social causes, outdoor adventure or education. Catalan kids are instilled in the values of association at an early age, gathering in casals and esplais in every neighbourhood. In these clubs they play or sing or go on hikes, but also organize themselves and do volunteer work. While the esplais’ 1920s origins were close to the scouting movement, they were always less vertical, inspired as they were by egalitarian socialist ideals of justice and community.

The ability of Catalans to meet for hours happily hashing through any concern, in business meetings or neighbourhood assemblies, has a lot to do with experience garnered in the esplais of their youth. Dialogue and blissful union, elsewhere so hard won, in Catalonia seem innate. As the culture of the esplai invades everything, everywhere you look, from TV3 to Junts pel Sí, everyone is bent on creating an image of one big happy family.

Life expectancy is 8 years higher in Sant Gervasi than the RavalThe problem arises when this culture of consonance obviates latent discord, and differences get washed over. Like social ones: as the gap between rich and poor widens in Barcelona, residents of Trinitat Nova and Marina earn 20% on average of what the wealthiest in Pedralbes pull in. Some children get just one proper meal a day, at school. Life expectancy is 8 years higher in Sant Gervasi than the Raval. It is hard to build consensus out of that without imposing it.

To be fair, many of those preaching harmony are nostalgically trying to recreate their teen years, so gleefully spent at the esplai. That is fine, as long as it is not a way of telling others (who maybe couldn’t afford to go) to shut up and stop complaining.